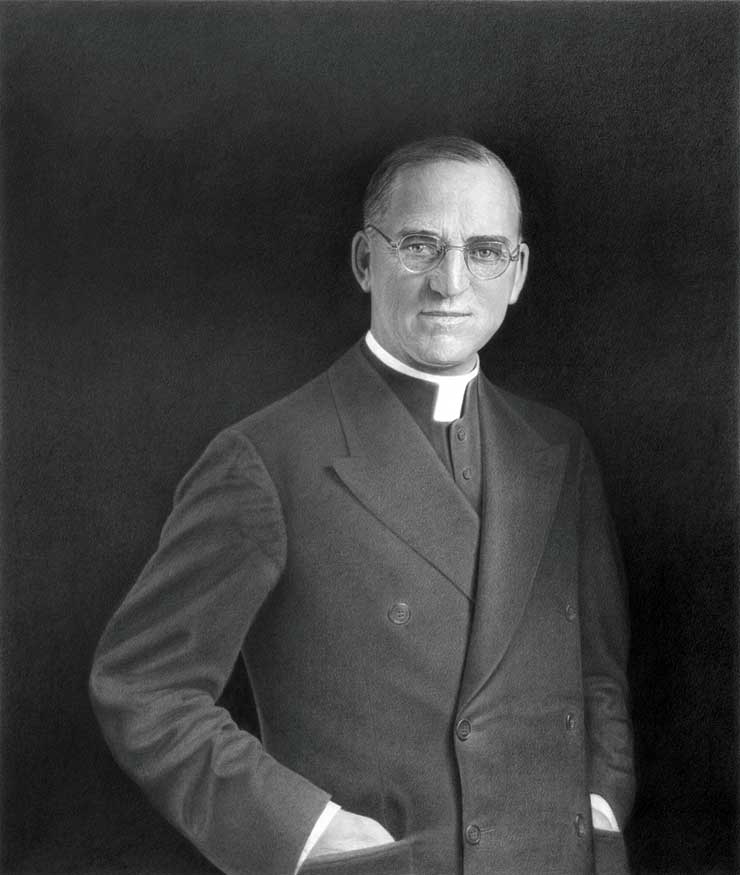

Servant of God Edward J. Flanagan's Message of Tolerance...A Man Ahead of His Time

Servant of God Edward J. Flanagan's Message of Tolerance...A Man Ahead of His Time

"I see no disaster threatening us because of any particular race, creed or color…but I do see danger for all in an ideology which discriminates against anyone politically or economically because he or she was born into the ‘wrong’ race, has skin of the ‘wrong’ color, or worships at the ‘wrong’ altar."

– Fr. Edward J. Flanagan

The following narrative was produced by the staff at Boys Town as part of a display reflecting on Servant of God Flanagan's "Message of Tolerance". It is worth reading and reflecting upon.

From the beginning, his Boys’ Home not only welcomed children of all races and religions, but treated them equally as well. Four years after the home’s founding, Father Flanagan purchased Overlook Farm, then ten miles distant from Omaha, and moved his boys to a relatively secluded acres – at least partially to escape the criticism and uneasiness of his city neighbors with his unorthodox methods of raising children.

Oscar Flakes, one of the first African-American boys at the home, remembered the tolerance encouraged among the boys: “We all slept together, ate together, played together, and fought together and everything. We were just ordinary kids.”

Oscar Flakes, one of the first African-American boys at the home, remembered the tolerance encouraged among the boys: “We all slept together, ate together, played together, and fought together and everything. We were just ordinary kids.”

But living on the farm didn’t isolate the boys completely from the sting of ignorance and prejudice. Flakes was a member of the “World’s Greatest Juvenile Entertainers,” a troupe of boys put together by Flanagan in the 1920’s to travel the Midwest, first by circus wagon and then by train, entertaining small town audiences with songs, skits, jokes, and speeches.

“I like to think of music as being the language of the soul.” said Flanagan. “It reveals to us the truth and beauty beyond the power of words to describe. Music goes beyond the barriers of race, creed, or geography. It is a spiritual medium of mutual fellowship for all people- for the rich and the poor, for the mighty and the meek, for the old and the young.”

Flanagan’s love of music and his belief in its healing powers led to the first of the Juvenile Entertainers and later a full-size band and choir. Away from the farm and on the road, the troupes performed; spreading word of the boys’ home and seeking donations to keep it running. In some places, town folk had never seen a racially mixed group.

“We went into [towns] where they hadn’t even seen a colored person,” according to Flakes. “In Beatrice, Nebraska, there were no colored at the time. When we gave a performance at night, some people would come up-people were very poor then and some of them couldn’t afford money, so they would take us and board us and feed us overnight. This little girl came up on the stage and would look at me. I know she was very small and very young compared to what we were. She would walk around me and go back to her mother. Finally, she brought her mother over, and she said (they were picking the kids they would like to stay overnight), ‘Mother, take him home and wash his face so that he will be clean like me.’ I remember that.”

Wherever the boys traveled, Flanagan insisted that all the boys be treated as they were at the home. At times, the troupe, and later the band, choir and sports teams would have invitations rescinded when it was learned the groups were integrated. One minister, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, threatened to tar and feather the group if it performed in his community.

Wherever the boys traveled, Flanagan insisted that all the boys be treated as they were at the home. At times, the troupe, and later the band, choir and sports teams would have invitations rescinded when it was learned the groups were integrated. One minister, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, threatened to tar and feather the group if it performed in his community.

But, sometimes, Father Flanagan’s message of tolerance made an impression. Flakes remembered an incident that took place in South Dakota: “Seven of us boys were there. We had come in the night-time late. When the morning came, we got up, Father Flanagan was with us. Anyway, we boys gave our order of what we wanted for breakfast and put our order in. When we all were ready to go down, we went together to the restaurant. I most generally brought up the back end because I liked to window shop and trail along behind.

“So when I came into this restaurant, the fellow said he wanted the little colored boy to eat in the kitchen. Father asked him why. He said, ‘Well we don’t serve any colored people in this town.’ That town only had three or four colored in it at that time. They were the janitors of the banks or the shoeshine fellows or something like that. Father said, ‘Okay.’ And we all went into the kitchen.

“Then the man said, ‘I don’t mean all of you – just the little colored boy.’ Father Flanagan turned around and said, ‘Well-if the boy can’t eat out [t]here, and we can’t eat in here, then we don’t eat here at all.’ He turned around and he left the food – they had the table all set and everything, the food was all cooked and waiting for us – and he walked out.”

“That same night, when we did our show, that restaurant owner came in and donated $500 to the cause.”

A few years before his death, Father Flanagan received a letter from a Michigan priest praising him for his “inner-racial good will” in the founding and running of his home. Father Flanagan replied: “I know when the idea of a boys’ home grew in my mind, I never thought of anything remarkable about taking in all of the races and all of the creeds. To me, they are all God’s children. They are my brothers. They are children of God. I must protect them to the best of my ability and these Negro boys have been just as fine and decent as the boys of my race and I have never suffered by too much criticism from any of my friends because of this inner-racial good will, which I must have as a Christian and a Catholic…”

“…I do not consider myself doing anything remarkable. I am only trying to do the Will of God.”

“Who am I that I should think that Christ, when he died on Calvary, died only for the Catholics living on millionaire row and white Catholics at that. My understanding of Catholic doctrine is that Christ died for the Negros, for the Mexicans, for the Germans and the Japanese, and for all the other nationalities, and why should I, therefore, set up a church, and become a dictator as a Pastor in that church, and say that my church is exclusively for the white race and that the Negro must not worship here. That would smack of an attitude of the Innkeepers when Mary and Joseph entered into the little town of Bethlehem and were greeted with the answer, ‘There is no room.’

“I think one of the most remarkable and outstanding results of the gift of Faith in the Negro is the fact that he has persevered in spite of the opposition he has received. He must be very close to Christ and he knows something of what the Cross that Christ carried, signifies. He carries it, he must know.”

Interview with Oscar Flakes, December 1988, Boys Town Hall of History archives.

Letter to Rev. J.E. Coogan, S.J. Detroit, Michigan, September 22, 1945, Boys Town Hall of History archives.